Not many developers and game makers have the resume of Giles Goddard. His work with Argonaut Games in the 1990s led him to move to Kyoto in his late teens to work with Nintendo on the now legendary Star Fox series. His impact on the video game scene is monumental enough that he had most of an episode of Netflix’s video game documentary High Score dedicated to his work on bringing 3D graphics to the sprite-heavy, 16-bit SNES alongside fellow Argonaut Games employee and Q-Games founder Dylan Cuthbert. But Giles is a lot more than Star Fox. For over two decades, Giles has worked within and as a subsidiary of Nintendo, opened his own company and is now the current CEO of indie developer and publisher Chuhai Labs. On the eve of the rebranded studio’s first anniversary, NME spoke with Giles about everything but Star Fox.

Prior to his independent move, Giles has credited in a whole host of Nintendo 64 titles. He famously programmed the stretchy face from hell that is the Mario 64 start screen, alongside other defining titles such as 1080° Snowboarding. But once Nintendo transitioned to the Gamecube, and Giles opened his own studio Vitei Backroom, his body of work seemed to diminish. That is thanks to Vitei’s role within Nintendo’s EAD (Entertainment Analysis & Development Division), as Giles explained to NME.

“At the time, we felt like we were a part of Nintendo EAD but in a different building in a different part of Kyoto. We were very well connected and always had some prototype progression going on. Someone at Nintendo would look at it and ask if we could do this and change that. We’d suggest things and praise other things. There was a constant back and forth of prototypes.”

Giles explained to me that, at first, this arrangement was perfect for Vitei. Around the turn of the century, there weren’t many indie game studios on the market. There wasn’t the vibrant community of players and developers alike to keep companies afloat off of their own backs. Having Nintendo pay a studio like Vitei to produce prototypes for their hardware is the perfect way to gain some independence without the financial risk. However, Giles explained to me a major drawback of this working arrangement and the reason his body of work seems to thin around this time.

“You can spend entire decades making prototypes with Nintendo because they fund those prototypes but they might not necessarily make games from them.”

Giles continued: “One [GameCube prototype] that particularly stands out was a puppets game, where you basically control the puppets against a backdrop of scenery that you put up there yourself. So the way you would get backlighting is that the player would have to physically place the lights in the scenery. So you would have a theme and then make a puppet show and the in-game audience would clap or boo depending on how well you were doing the performance. It was great fun, and Nintendo thought it was a great prototype but they didn’t see the potential to make it a mass-market game. It is my favourite prototype I have ever worked on.”

This prototype was being developed around the same time that a “Mario-nette” title was rumoured to be working on – a game that blended Mario with puppetry. Considering how the Mario IP has been warped and changed over the years, it wouldn’t have been a stretch to see Mario utilised within the realms of this prototype. However, as Giles told me, “no matter how good the prototype is from a second-party, early indie studio. Giving them an IP like Mario was just impossible.”

Giles continued to tell me that during this time, stretching through the Gamecube right into the Nintendo Wii era, Vitei worked on “15 or 20 prototypes for potentially really great games that could have come out.” One, in particular, represents a particularly painful missed opportunity for Giles.

“I had a frisbee game I really wanted to make for the Wii. It’s one of my biggest regrets not pushing for that frisbee game harder. When the Wii released the Wiimote+, it had accelerometers, sixth-axis and could detect your position much more accurately. That would have been perfect for a frisbee game and I am a huge frisbee guy so there were lots of those more interactive games I wanted to make with the controllers post-GameCube.”

Even though there is clear frustration within Giles about some of these missed opportunities, this hasn’t soured his love for Nintendo hardware. Some of Vitei’s success stories come via Nintendo’s smash-hit handheld, the DS. Titles like Steel Diver and sequel Steel Diver: Sub Wars managed to utilise the DS’s unique split-screen hardware to great effect. Giles spoke to me about the unique approach a developer has to take when working with the Japanese giant.

“With almost all Nintendo hardware, they always try to get developers to make games to specifically fit the hardware. Whether that be the two screens of a DS or a remote you can move around. They always try to make the developers utilise the controls and display as much as possible. So, with the DS the main question was how can we use two screens? So, you would always be compromising with the things you can do with the hardware at all the points.”

He adds: “That has always been the most interesting thing about Nintendo hardware. Ask yourself: “with the available hardware you have, how do you compromise to make the game possible?” They always make the most interesting hardware. Taking two screens and making that into a console, nobody in their right mind would do that. It’s an insane idea! But it forces the developer to think “how do I change the concept of what a game is based on this hardware?” I have always liked that aspect of the way Nintendo makes games.”

This constant problem solving has gone on to shape Giles’ approach to making games generally.

“For me, game design has always been about hardware driving the game design. That’s where you get the interesting ideas, you get a new piece of kit, you try new ideas out and think “alright, based on this new way of making games, I can now make this game I could never make before.” That has always been the most interesting part, for me personally, about game design.”

So now we live in 2021, where hardware limitations are borderline non-existent. With home consoles having millions of times more processing power than consoles of old, what are the key challenges to making games today? For Giles, that answer is simple: game engines.

“When it comes to limitations, it’s usually software that is the limiting factor, not the hardware. Especially with things like Unreal and Unity. Because, as a developer, you have no control over how it’s made, you just have to use it. So if it doesn’t work, there’s nothing you can do about it.

“In the past, we made all of our own engines but now we have to use Unreal or Unity or whatever. When you make your own engine, you know exactly how it worked. So if there was a problem, you would know what was wrong with it and how to fix it. If Unreal or Unity breaks, it’s difficult to find out why it has broken and that can be very frustrating. Also, when we made engines we would also tailor the performance for each game, which you just can’t do with off-the-wall products.”

Giles goes on to explain that it is possible to take a black-box engine like Unreal and create a more bespoke product, citing 17-bit’s recent VR title Song In The Smoke as a shining example of this, but Giles tells me that this process is “very time consuming, very painful. It’s not ideal.”

However, for all the pain that using a modern game engine can give you, Giles does confess that these tools does make the initial prototype phase easier. This very early stage of development, before any textures, graphics or user interfaces are programmed in is, according to Giles, one of the most important parts of creating a great game.

“Engines like Unreal and Unity make the initial prototype very easy to figure out whether it will be a good game or not. Whatever hardware you have, whatever APIs or game engine you’re using, you can still make a basic game out of it and you know quite quickly whether it will be good or not. Forget about graphics and everything, just find out whether there is a game there or not. That has always been my philosophy.”

That philosophy has guided Giles through the early years of Vitei and now through to Chuhai Labs, the rebrand of the Vitei name. One year into this project, Chuhai Labs has already helped publish the delightfully spooky platformer Halloween Forever, are developing the much anticipated Cursed To Golf, which has been previewed by NME and released a spiritual successor to one of Giles’ most iconic titles with VR game Carve Snowboarding. Carve and 1080° Snowboarding are some of Giles’ most accomplished works – making the very kinetic experience of snowboarding feel good through a controller and headset. It’s his work on these titles that brings Giles significant pride. Not only for their success, but the problem solving needed to make the mechanics work in the first place.

“The thing I am probably most proud of is the horribly complicated physics that I made for the snowboard. People think it’s programmed as a snowboard, but actually, it’s a 4-wheeled car that’s going down the slope, and the snowboard is sliding around inside that car. It was the only way I could work out how to make the rotations that helped actuate you on the slope was by having the 4 clear points of the car as reference. I think that’s the thing that stands out the most. Interestingly enough, when we were making Carve we used a very similar system. But rather than 4 points this time it was just 2 points and you control the tilt.”

“I think the thing that stands out most for me was that you could take something that people think is an extremely complicated gameplay mechanic and just simplify it down to very basic components. It doesn’t matter how complex it is, if it feels right it feels right. For physics games, it’s all about that feel.”

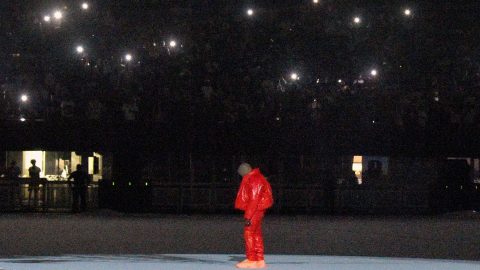

Giles Goddard is an industry legend. There’s no denying his monumental impact on the medium we love. But what is so striking about speaking with him is not only his passion for the things he makes and the obvious wealth of knowledge he has about game creation, but the distinct lack of arrogance or pomposity surrounding him. He made Star Fox, he has every right to sing about this to the high heavens. But Giles is a creator who chooses not to be defined by just one project, or using that clout to propel himself into every conversation about the world’s most successful programmers. Instead, Giles celebrates the people around him at Chuhai Labs. Instead of glitzy 1-year anniversary celebrations broadcasted with his name and image splashed everywhere, he hosts a party for friends, standing around a BBQ cooking yakitori. Chatting about the industry that, after all this time, he still loves. With reckless abandon.

Michael Weber is a freelance journalist based in Japan, and frequent contributor to NME

The post Industry legend Giles Goddard discusses everything but ‘Star Fox’ appeared first on NME.