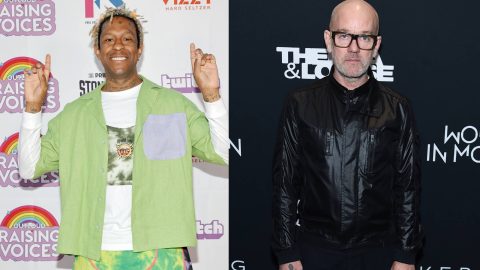

Teddy Dief fell into the games industry “backwards and sideways” but now, they’re on top. After a rocky start to their game development career in New York, Dief said “fuck gaming, this place is terrible” and flew to L.A with film school on their mind.

And yet, they still became one of the games industry’s leading creatives. Not only did Dief produce Heart Machine’s critically acclaimed action role-playing game (RPG) Hyper Light Drifter, they also founded charity stream-a-thon Chocobowl, co-created L.A. game maker’s collective Glitch City, and spent time as creative director at Square Enix. Last month, Dief released We Are OFK: a touching visual novel that I’d already fallen in love with thanks to its profound exploration of what it means to create something.

But long before Dief was sweeping award shows and basking in critical acclaim, they were spending their childhood “living in” Square Enix’s 1997 genre-defining role-playing game (RPG) Final Fantasy.

“I remember playing Final Fantasy 7 and there’s a scene where somebody gets kidnapped, and you’re supposed to be all sad. I just walked my character up to the window and dramatically looked out out for a few minutes. It’s such a performative thing to be performing for no one but the world that I’m in,” says Dief. “I have always found games that let me live in it for awhile get my imagination going the most, and it’s a more transformative experience. Maybe it’s not escapism, but I just like to engage with things in that way.”

“Sometimes it’s good to put your head down and work and not get input, but emotionally it sucks. You’re like, what am I doing?”

Dief, adds that Square Enix’s 1993 classic Secret Of Mana also played a large part in their development. “Secret Of Mana is an action RPG – so you can move around and feel like you’re always in control, and feel like a little bit more connected – more involved – with these characters. That was something that eventually led me to decide to work with the Hyper Light Drifter team, because it felt like my chance to make Secret Of Mana, but make it feel better.”

Their journey into game development began in New York, but started off on a bad foot when they found “unpleasant, predatory companies” and subsequently “moved out to L.A to go to film school.” However, Dief – who juggled writing, singing, acting and directing on We Are OFK – has never been one to stick with a single creative outlet, and it wasn’t long before they found their film school’s games programme. “Film felt so enclosed and dogmatic,” shares Dief. “You can make a web series, but no one’s going to pay you for a web series!”

In L.A, Dief thrived. In 2015, they co-founded Chocobowl – a 48-hour livestream that pits game developers against their favourite Japanese role-playing games (JRPGs). They came up with the idea while spending time in L.A. with one of their “dearest friends in the world,” Among Us developer and OFK collaborator Adriel Wallick.

“We were watching Games Done Quick – an incredible charity stream – and felt like we wanted to do that, but slowly and without any professional ability to do it well,” laughs Dief. “I had never done anything like streaming before– I had no experience with Twitch – but the idea of taking this game we really like that I don’t have time to play anymore – because I make games now – and sitting down and having a community talk and playing felt really interesting. It felt like one of these nice moments of watching games reach outside of themselves to become a larger ecosystem.

After the first year of Chocobowl, the founders decided to use the platform to raise money for charity, and has since raised tens of thousands for organisations including AbleGamers and The Bail Project. “We felt we didn’t really need the attention, so poured it into something that does,” explains Dief.

Between Chocobowl and Glitch City, it can be hard to imagine L.A.’s bustling creative games scene without its beloved game developer. For Dief and the co-founders of Glitch City, the L.A. collective was a way to bring the city’s scattered development community together.

“Before we all started Glitch City, we didn’t really know that there was a community in LA – or at least I didn’t, which is funny because it’s the second biggest city in the US for games,” recalls Dief. “But LA is so spread out, and so all of us who were doing independent games from our bedrooms had no clue that we were all out there.”

“I wouldn’t know how to make anything – emotionally or creatively – without other people in the room”

“We’d all been meeting for this thing called Strawberry Jam,” recalls Dief, referencing an event where indie developers would come together at the city’s coffee shops to make games. “That just very quickly became not viable,” they continue. “We wanted something that was more stable, so we had a big roundtable meeting at some point. We’re all here, figuring it out and trying to make our little games, and we all have just a little bit of savings – how much money can we pool together to rent a place for a year, for ourselves? Cause nobody’s gonna rent a place to a bunch of weirdos!”

However, armed with a spreadsheet and a dream, the founders of Glitch City found their own space. “It very quickly grew to fill a similar need that a lot of people had for social connection and support, and finding other like-minded creative people – not just in games, but around games,” says Dief. “We started to do poetry nights, and art nights, and little concerts – and when other indie game creators would come into town, they would be looking for an anchor because Los Angeles is such a strange place to visit.”

Glitch City is coming up on its ten-year anniversary, and Dief acknowledges that “the same thing that has kept it alive has also kept it small – a healthy tension between founding members for what our priorities are.”

“I love events, so I was always trying to be involved in that,” reflects Dief on their own role in Glitch City’s success. “I was a social butterfly person, and it was to the credit of the other founders who have provided a balance to that. They didn’t want to grow – I’m grateful for a lot of the scepticism that some of the founders had around accepting money. A couple of big companies approached us over the years about trying to fund the space and sponsor the space, and I have such twinkles in my eyes for the potential of things. It’s always things I want Glitch City to be able to do, but it’s the collective hesitance at taking money and having a corporation connected that’s kept us alive.”

“I guess what I’m saying is, Glitch City is alive in spite of me,” jokes Dief, who says working with fellow members Ben Esposito and Brendon Chung created a “nice, perfect size of aspiration” for the collective. Dief’s involvement in L.A.’s scene says a lot about their approach to creating something – Chocobowl and Glitch City are both community-oriented and promote collaboration, and Dief has worked with developers involved in both projects to create Hyper Light Drifter and We Are OFK. Throughout our interview, Dief makes a point of naming friends and co-workers who made each of their achievements possible, and it becomes apparent that collaborating with others is something the developer holds dearly. When it’s brought up, Dief agrees that they thrive on collaboration.

“I look to collaboration for two reasons,” explains Dief. “One is that I love it when people are better than me at things – time and time again, I aspire to be one of those solo devs that could do everything and be this fuckin’ auteur. But I would rather see human beings and I would rather have a mixture of ideas coming together. With OFK, for example, every time someone came into the project it would transform a little bit. There’s only so far I feel like I can take any idea, and then I just want other brains to come in and look at it. That’s the nature of it.”

“The other half of it is it’s so fucking hard to be confident, and to stick with something and believe in something. Some people can have the outright confidence and tempered narcissism to be like, this is gold. Maybe I have a low simmering amount of narcissism that I try to keep in check, but every time one of these people comes down to the project, and agrees to work on it and agrees to give their limited time – the most valuable resource we have – it’s a stamp of approval ,it’s saying ‘I think this is cool’. I look to these people to be like, well if I think they’re so cool and talented and they’re working on this, then maybe I’m doing OK and maybe let’s go to the next step. I wouldn’t know how to make anything – emotionally or creatively – without other people in the room.”

Dief’s portfolio is a testament to their team-oriented approach. 2016’s Hyper Light Drifter, an RPG inspired by Heart Machine’s favourite 16bit titles, was made alongside several developers from Glitch City – including Alx Preston and Beau Blyth. The game is brilliant – it’s even getting a sequel – and Dief explains that their role as producer on the game meant trying to ensure every team member’s voice was heard. However, despite Hyper Light Drifter’s enthusiastic reception and slew of prestigious award nominations, Dief recalls being left with mixed emotions over how it was made.

“There was a thing I felt after we finished Hyper Light Drifter that felt bad to me. The feedback loop on making a video game is so slow. You work on something for years, and every video game is supposed to take a year and a half, and it takes four [years], time and time again. Sometimes it’s good to put your head down and work and not get input, but emotionally it sucks. You’re like, what am I doing? Why is the life that I’ve chosen? I’m trying to make art, which to me is meant to connect with people, to see people and be seen, and yet I’m hiding in this room pulling the blinds down so that I can see my monitor better.”

“After the three-year production of Hyper Light Drifter, getting to finally hear what the audience thinks and how it strikes them, or what it means to them just didn’t work for me emotionally. We got all the things we say you want – all the good reviews and awards and all that shit – but it was too late. I’m grateful for it, but emotionally it was too late – I’d already moved on from the process of making that thing.”

Dief adds that they prefer the much more reactive feedback loop within music and performance, where someone in the same room as you can offer immediate input. That ties into Dief’s latest game, a musical narrative titled We Are OFK. Dief says that “having multiple ways of engaging with people in OFK, for me, is partially a response to that,” as it allows them to “make these things that require big ideas, teams and coordination, but also be able to just talk directly to people and react.”

“I have always found games that let me live in it for awhile get my imagination going the most”

Later that day, Dief says they’re scheduled to stream on Twitch as We Are OFK’s Luca, a character that they lend their voice to. On bringing OFK’s characters to life, Dief explains that “I spent most of my time thinking about my interactions with other people. I’m mostly thinking about what other people are thinking because of my own anxieties.”

“It’s kind of similar – the creation of a character is different, but being in different headspaces is something I do anyway. For my contribution to the story, each of the characters has imbued in them something about myself that I enjoy, and something about myself that I am critical of, or ashamed of. It [helps bridge] me to a character, to think about what we have in common – what we struggle with, what we aspire to be better at. The more I can take that premise of a character and chop them up and divide those different feelings into different characters, mould that clay in with people and other sorts of personalities I’ve met over time. No character is ever just one person I’ve met, and no one character is ever just me. It’s always just an amalgamation of trying to understand people, and I like being in other people’s heads.”

“Whenever someone asks ‘what’s your target audience?’ Or, ‘What’s the moral of the story?’ [I don’t know] – I feel like if I knew the moral of the story, I could go ahead and die and say I figured out life!” continues Dief. “ That being said, I think collaboration is the central theme of both the creation and story of OFK.”

One of Luca’s lines in OFK – “I want to be better than I am” – resonates closely with Dief. “For me, the hardest part of being an artist – whatever that word means – is that you want to connect with people by being like: here’s who I am, see me! I’m not sure why I need you to see me – it’s something to do with death and mortality.”

At this point, our conversation takes a detour as I realise Dief’s existential crisis is contagious. For those of us with creative outlets, the compulsion to express ourselves feels natural – but as Dief scratches beneath the surface to ask why we feel this way, it raises questions that are difficult to answer. Why isn’t merely putting something out there into the world enough for us? Do we want to create something new, or are we just subconsciously searching for approval? “I’m glad we’re having a crisis together,” Dief reassures me.

“I want to be seen and I want to see other people, and I want to know who’s out there who maybe understands me,” explains Dief. “While you’re doing that you’re also self-critical. It’s our job to be thinking about…is my music good, or is my writing good? How can it be better? All on top of like, how can I be a better person? How can I make people more comfortable, or be more attractive to people, or tell a joke that people think is funny? I think about it all the time. I just have to strike a balance between wanting to be proud of who I am in life and also accept that I’m always wanting to be better – never knowing what that means.”

For Dief, creating their best work often involves being at the helm of a project. “There’s no such thing as a good boss, but I’m trying to be a good leader because I need people, and I want to be good to them”. However, that sense of responsibility proved challenging to Dief when they were elevated to their most mainstream role yet: a creative director at Square Enix.

On paper, it sounded like the developer’s dream: to be given the “captain’s chair” at the company responsible for Dief’s favourite childhood games. But it was a huge shift as not only was it a departure from the smaller development teams Dief was used to working with, it meant leaving behind L.A. and moving to Montreal. That change was so dramatic that Dief remembers friends reacting in “disbelief” to their new role, even as the newly-titled creative director felt the job was “too good to be true.”

“ I love it when people are better than me at things”

In a way, it was. After working at Square Enix for several years, the project that Dief’s team was working on was cancelled by higher-ups at the company. Dief was left feeling “so angry” after the cancellation, and remembers being told it was a “violent thing to have a project killed.”

“When you’re working for a company, a project being cancelled is a project being killed because you can’t use it – the company owns it, so it is dead. The characters we wrote were dead, the story was gone, the mechanics were decimated,” says Dief. “I processed what it was – a loss. My trust was destroyed in the environment that we work in, my drive to make things was gone. I didn’t lose two years of my life, but I lost two years of my work and of my team’s work.”

Dief adds that it was “so painful” to have the decision passed down from above, but it offered an important lesson on producing games. “Working at Square taught me time is the most valuable resource, and money doesn’t care about time – Indie games are not immune to that. I moved to a new country for that project. Other people moved to a new country for that project for me. When that project was taken from us, I felt anger and frustration for myself, but such a feeling of shame at having let these people down. None of them lost their jobs – at least they have that – but they lost their work, and they lost their time. It made me more acutely aware that you’ve got to get outside your own head and realise, these people that are working with you are giving their time and they’re having the same anxieties. That is both a validation of the project and a huge fucking responsibility.”

After leaving Square, Dief says they “fucked off and “went to live nomadically,” trying “to learn the skills I didn’t know, so I could make everything myself”. However, as painful as the cancelled project was, Dief’s drive to collaborate helped them find peace – even if they knew the game would never be made. “For me, projects come up around the people that join it, and they transform the projects. When I’m talking about losing the project, I’m losing about losing that team,” says Dief. They add that they have had conversations with friends about reviving the project in a similar (and legal) way, but say they “wouldn’t want to because the team’s gone. Why would I make this thing that was ours, when there’s no us anymore?”

Dief was drawn from their solitude – perhaps predictably – when “people lifted me out of it”. They eventually returned to LA, “tinkering” with some ideas – and although Dief says it initially felt like betraying their old team at Square, it wasn’t long before they were immersed in a smaller indie team again. Dief says it “felt good – like home” to be making something with others again, and although their time at Square Enix left them “skeptical of big environments,” they say some of the same views they put into their Square project made it into OFK. As a result, Dief’s latest game says a lot about their philosophy, about the one thing that’s followed them through their career: collaboration.

“I hope that the story speaks for itself, but I will say that this project was transformed by the people that work on it, and the focus is on what comes from the people,” continues Dief. “The story is about people and how they work together, and what they need, what they want to do, aspire to do, and what they’re unable to do. There are all these micro-stories and characters in that game that are just speaking to different challenges and dreams that we have. It’s this patchwork of what it feels like to be making things.”

Wearing their passion for collaboration openly, Dief has brought together LA’s games industry with a warmth befitting the sun-soaked West Coast. While it remains to be seen where the developer goes next, the story behind We Are OFK’s creation suggests they won’t be going alone. “People were starting to ask me to just have a vision,” reflects Dief. “I can’t have a vision without people…and that became the whole story.”

For more information about We Are OFK, click here

The post Teddy Dief can’t do this alone appeared first on NME.